When it comes to restarting a mine, there are a few important elements that need to be addressed first to ensure success.

Even with good intentions and a seemingly concrete plan of action, market shifts and commodity crashes can lead a mine to close.

While many mines manage to be successful, profitable operations for everyone involved, others don’t always pan out as planned. Factors ranging from a company’s balance sheet to geopolitical issues can cause a mine to have its operations halted, be put on care and maintenance or, in other cases, abandoned entirely.

On the other hand, sometimes a company will opt to breathe new life into an old mine. When a mine is revived, it can often come after the asset changes hands, with the new owner putting direct focus into renewing its worth. Other times, if a commodity’s price point makes a comeback, the original owners will choose to give their mine another shot.

However, before one can cross into restart territory, it’s important to examine the reasons that the operation shut down in the first place. Read on to get a better idea of why mines close and what it takes to bring them back to life.

Why mines close

As mentioned, if a commodity finds itself in a precarious pricing situation, the mines that focus around that metal or material can struggle in a domino effect. The price of a commodity can fluctuate for a number of reasons, including global trade wars, turmoil in major producing countries and the always ongoing game of supply and demand.

According to Leah Wong, senior issues and media advisor for Ontario’s Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines, the mining industry can be just as vulnerable to volatility as other sectors.

“Not unlike other global industries, mining is subject to impacts of global market conditions and variation in commodity prices for the product produced,” Wong told the Investing News Network (INN). “Different commodities may be subject to different market forces; however, almost all commodities are subject to global market forces.”

Commodity pricing aside, she went on to say there are several valid reasons for a project to shut down.

“There are a variety of reasons that a mining project could come to an end, including but not limited to changing mineral prices over an extended period of time, which renders the project unprofitable, the mineral resource has been exhausted and thus the life of mine has come to an end or financial hardship of the company.”

Echoing similar sentiments was Jeff Plate, vice president of marketing and business development at Watts, Griffis and McOuat (WGM), who laid out the three most common mistakes his firm sees when a company tries either restarting a mine or getting a new one up and running.

“The three most common mistakes we see are insufficient technical work to de-risk the project and ensure a full understanding of the production and costs of a mine, undercapitalization of the project, a lack of sensitivity analysis, which stress tests the mine and its operations under a series of real-world conditions (and) unrealistic expectations or completion schedules for starting or restarting operations.”

The keys to a successful restart

While the task of taking on a historical asset can seem daunting, experts say there are a few fundamental boxes to check off in the process to ensure everything runs smoothly. According to Plate, doing one’s homework on why a mine initially closed is an essential place to start.

“Understanding the elements around the shutdown is critical. Has the new project manager and mine operator carried out sufficient work and analysis to understand the past reasons for closure and have all current regulatory, social and permitting requirements been factored into economic models?” he said.

“WGM has seen many projects where a fatal flaw analysis is not completed by competent independent professionals in order to save money or speed up the return to production. While this may be appealing to short-term financial metrics and to securing investment, it leaves the venture subject to significant risks and repeating the mistakes of the past.”

Clint Donkin, president of global asset operations at Ausenco, had similar input to Plate as he highlighted the importance of a company thoroughly weighing the pros, cons and different working parts surrounding a mine.

“A company really needs to approach it the same way as you would for a new greenfield project, because, ultimately, the risks and opportunities are very similar,” Donkin told INN. “They need to determine at the very start if an ongoing operation is feasible and sustainable. I think it’s important that they learn and understand the history, and can demonstrate that the business model (they’ve got) is robust and that the risks are well understood and managed.”

Donkin went on to explain that another important factor when rebooting a mine is to have a strong, experienced leadership team running the show. He added that investing in local communities early to obtain their social license can also be incredibly beneficial for the success of any project.

As Wong said, no commodity is completely safe from the ripple effect of market volatility when there are often several variables that affect pricing. However, that’s not to say there aren’t ways of playing one’s cards strategically when it comes to choosing which mine to acquire — and when one does it.

One benefit to restarting a previously operational mine, according to Donkin, is not only the likelihood of pre-existing infrastructure but also the ability for curious investors to keep an eye on a commodity’s status in the marketplace before heading down the acquisition path.

“The companies, depending on their execution strategy, can bring the operation back online in typically far shorter periods of time than what you typically could for a greenfield project. So the nice thing there is that you could really get your timing right for your re-entry into the market to fully leverage the market conditions and commodity prices.”

Historical examples

As with Donkin’s point about finding the right opportunity to restart a mine, some companies choose to play the waiting game in hopes of a commodity’s pricing making a turn around. Evidence of that can be seen in a large chunk of the nickel space right now, as many companies are starting to acquire past-producing mines or revamp their own prior operations.

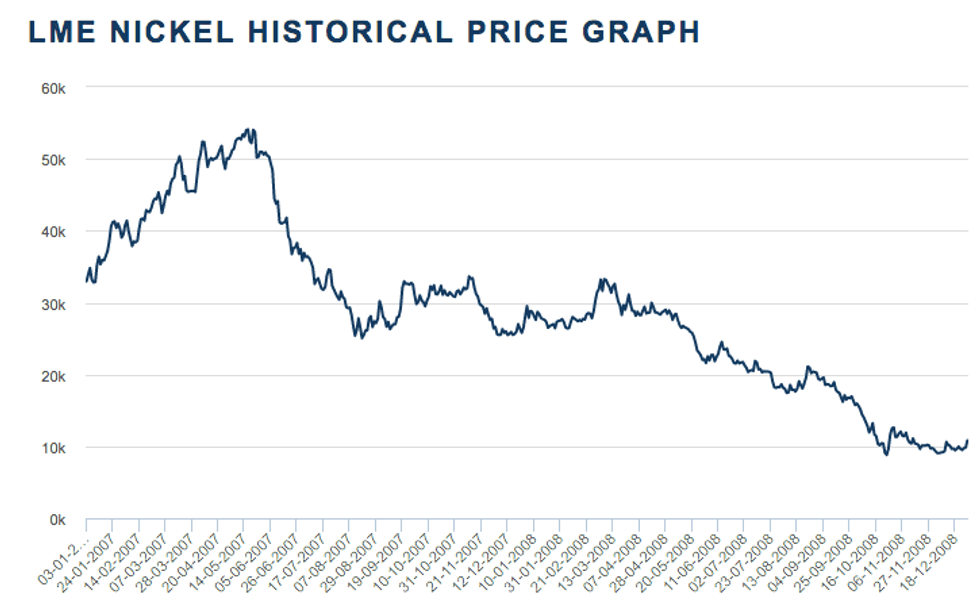

Between the beginning of 2007 and the end of 2008, the base metal took a historically heavy dive on the markets; for reference, its peak high during this time was US$53,730 per tonne on the London Metal Exchange. That number would later collapse to US$8,805 by October of 2008.

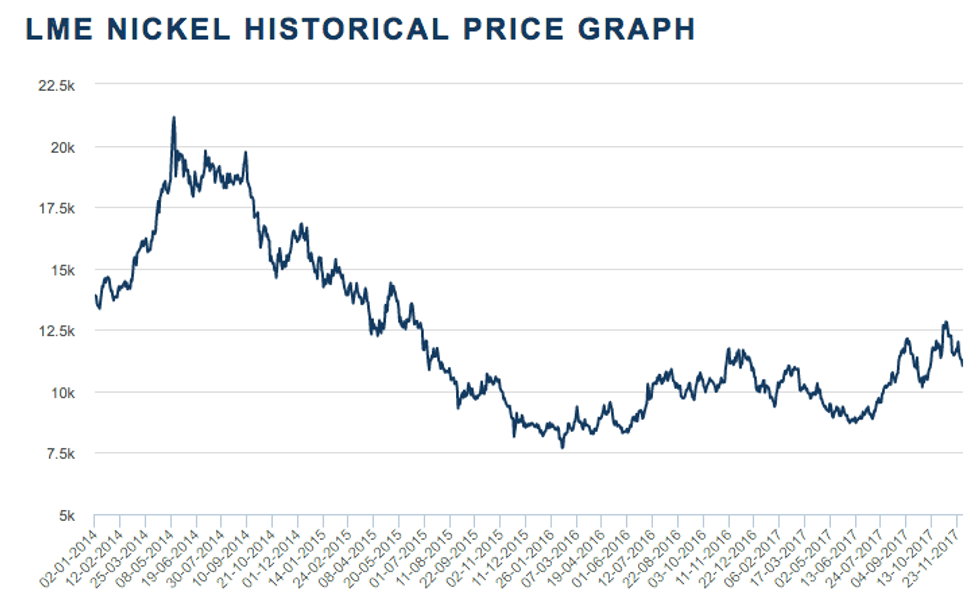

While the commodity managed to eventually rally from those lows, it faced another rough go between 2014 and 2016 that saw pricing fall from highs of US$21,150 to as low as US$7,715.

As to be expected, many nickel producers found themselves closing up shop during this time as their prized commodity’s pricing burned to the ground for the second time in a decade.

However, since then the nickel price has made somewhat of a comeback; it hasn’t quite reached the highs it held in 2007, but has generally trended upward. For comparison, nickel was trading at US$12,210 on the LME as of May 16, 2019. This can be partly attributed to its role in the electric vehicle revolution, or, more specifically, its presence in lithium-ion batteries.

Alongside nickel’s pricing making a return are the former producers, including Panoramic Resources (ASX:PAN,OTC Pink:PANRF) with its coveted Savannah project. The company touts itself as being 100 percent focused on the mine in Western Australia, which operated from 2004 to 2016 and produced over 180,000 tonnes of nickel.

The asset was put on care and maintenance in May 2016. However, by July 2018, the company had formally decided to restart operations at Savannah. Since then, it has been laser focused on the asset’s revival, with Panoramic achieving its first shipment of bulk concentrate since the closure in February.

In a similar boat is Mincor Resources (ASX:MCR,OTC Pink:MCRZF), which produced around 180,000 tonnes of nickel from Western Australia’s Kambalda district over 14 years. However, the company also placed its operations on care and maintenance in 2016 due to nickel’s shattered price point.

Since then, the company has begun its “nickel restart strategy,” which focuses on four deposits in Kambalda; in March, Mincor locked down an offtake term sheet with BHP’s (ASX:BHP,NYSE:BHP,LSE:BHP) Nickel West for nickel sulfide ore processing.

As with any investment, there is always an element of risk and reward to acquiring a mine, even when it comes pre-packaged with bells and whistles like pre-existing infrastructure. However, with the right combination of doing your research, getting your timing right and having a good eye for market trends, the pros can prove to be far greater than the potential cons.

Don’t forget to follow us @INN_Resource for real-time updates!

Securities Disclosure: I, Olivia Da Silva, hold no direct investment interest in any company mentioned in this article.

Editorial Disclosure: The Investing News Network does not guarantee the accuracy or thoroughness of the information reported in the interviews it conducts. The opinions expressed in these interviews do not reflect the opinions of the Investing News Network and do not constitute investment advice. All readers are encouraged to perform their own due diligence.