These three unique attributes explain why central banks remain large and growing holders of the metal.

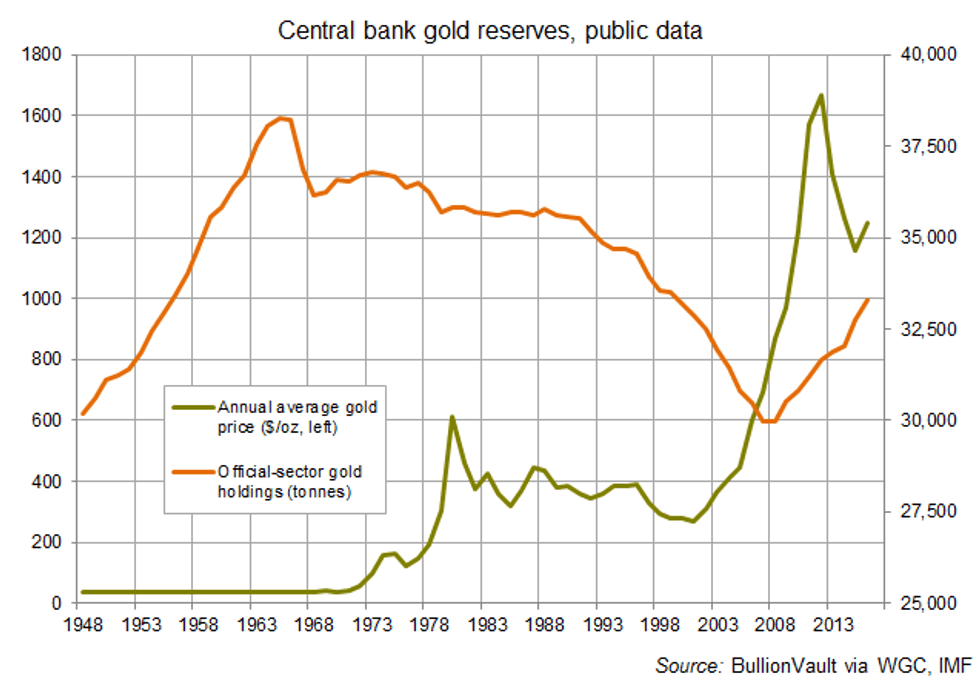

Reserve managers as a group last year grew their gold holdings to the largest since 1999. Official sector holdings have now recovered half the outflows of the previous four decades, rising above 33,000 tonnes when figures for global authorities such as the International Monetary Fund are included. State players today own almost one ounce in every five ever mined in history.

But this growth in central bank holdings masks divergent trends. According to the best estimates, 2016 also saw the smallest net increase since 2010. So while analysts expect the official sector to remain a net buyer again in 2017, its call on the gold market — averaging some 10 percent of total demand so far this decade — cannot be taken for granted.

Does that matter to prices? The size of central bank gold demand shows no consistent correlation with market direction. On a rolling four-quarter basis, in fact, public data show a negative relationship with prices since the turn of the century; that is because central banks as a group have tended to buy more when prices fell and less when gold rose. But sentiment matters to investment demand — the key driver of price gains or losses — and it’s a fact that gold’s long 20-year bear market starting in 1980 culminated with heavy selling by European holders. The surge to 2011’s record highs then coincided with a jump in emerging-market demand, led by India, Russia and China.

Formerly the number-one buyer of the last 10 years, the People’s Bank of China has now failed to add any gold to its publicly reported currency reserves since October 2016. Guesswork says Beijing had no need to keep buying gold once its reserves — the fifth-largest national hoard — helped secure the yuan’s place in the International Monetary Fund’s basket of top currencies last September. The politburo may also feel China’s world-leading gold miners no longer need any official assistance after the sharp 2014-to-2015 drop in the country’s world-leading private demand. But a simpler and more urgent cause might be Beijing’s sharp outflow of foreign currency, with a threat of “capital flight” by foreign and domestic investors forcing the central bank to shrink its huge foreign exchange reserves by 7 percent last year.

Either way, China’s lull has put Russia in the top slot amongst central bank buyers. Moscow bought gold in 141 of the 180 months leading up to June 2017, accumulating an additional 1,260 tonnes over 15 years to come one place behind China in the world table. More than half of those inflows have come since spring 2014, when European and US sanctions over Russia’s annexation of Crimea first blocked inflows of foreign investment capital and then squeezed sales of Russia-mined gold abroad. In this, Moscow has repeated the tactic used by apartheid-era South Africa, also then a major producer. Russia has now come in the top three producer nations each year since 2013, and buying direct from Russian miners for rubles enables Moscow to aid a key domestic industry while growing its central bank assets in the absence of foreign exchange inflows.

Little wonder that Russia’s demand also shows “a desire to diversify reserves away from US Treasuries,” notes the Gold Survey 2017 from specialist analysts Thomson Reuters GFMS, “plus a positive view of the prospects for gold.” Such motives also seem key to Central Asia’s other big buyer, fellow gold-mining nation Kazakhstan. Smaller consumer nations in contrast paused and even reversed their previous buying last year, with gross sales rising 15 percent from 2015 to reach the heaviest level since 2010.

Profit taking and so-called “dynamic hedging” led this move, with reserve managers looking to book gains and rebalance their portfolios across other assets on mid-2016’s Brexit price spike to three-year highs. Even with net buying down 35 percent as a result, however, central bank demand “remained high by historical standards,” says consultancy Metals Focus, again stressing “a desire to diversify away from largely US Dollar-denominated reserves” as well as gold’s proven appeal amid growing “geopolitical risks.”

“First, security,” explained Banque de France Manager Hervé Hannoun in a speech in 2000. “The absence of any credit risk is an intrinsic quality of gold.” Next comes liquidity because “in situations of political turmoil or high global inflation, gold’s liquidity is unchallenged,” he went on. Last but not least comes diversification. “Unlike most other assets, gold prices go up when things go wrong,” Hannoun noted. “So gold is very useful [because] it enables you to improve your risk/return profile.”

These unique attributes explain why, more than 45 years after the US severed gold’s remaining ties to the world’s day-to-day money, central banks remain large and growing holders of the metal. Those same benefits also make gold a form of investment “insurance” for private savers and larger money managers.

By Adrian Ash, BullionVault