Is Vanadium the Energy Storage Solution of the Future? - Part 1

Part one of our three-part vanadium series focuses on the invention, use and applications of vanadium as an energy storage unit.

Vanadium is an abundant silvery-gray metal, cousin to niobium and tantalum, that is primarily mined in China, Russia, South Africa and Brazil. Part one of our vanadium coverage will focus on the invention, use and applications of vanadium batteries.

While there has been a lot of discussion around which metals will be used in electric vehicle (EV) batteries, predominantly in the nickel, cobalt and lithium space, the EV sector isn’t the only one that needs to secure a long term sustainable, green and efficient energy supply.

Vanadium has been pegged as an up and coming energy storage metal especially in relation to large scale applications due to its ability to store extensive amounts of energy.

Invented decades ago, vanadium redox flow batteries, or VRFBs, have only recently gained popularity as a contender for large scale energy storage. VRFBs are a viable option for large scale storage because they are able to provide hundreds of megawatt hours at grid scale. Meaning, they are able to be charged thousands of times without losing capacity, while holding large amounts of energy.

How it works

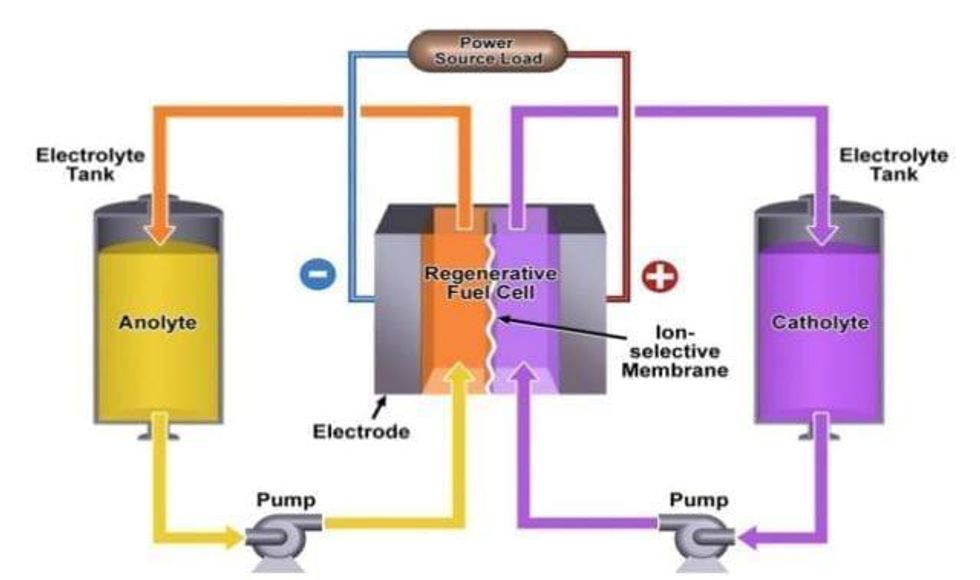

The positive and negative sides of a vanadium redox-flow battery are separated by a membrane that selectively allows protons to pass through. While charging, the applied voltage causes vanadium ions to lose one electron each on the positive side. The freed electrons flow through the outside circuit to the negative side, where they are stored.

During use, those stored electrons are released, allowing them to flow back through the outside circuit to the positive side.

Image: US Department of Energy

Since their inception in 1984, VRFBs have slowly advanced and refined their storage capacity and delivery technique. The first generation of vanadium batteries weren’t able to hold much energy, roughly 12 to 15 watt-hours per liter of electrolyte.

In order to perform, the batteries had to be extremely large, approximately the size of a one or two basketball courts, making them an unrealistic energy solution.

In the 30 plus years since then, VRFBs have come a long way. Today’s vanadium batteries are produced in high tech giga-factories, and are a third of the size as the gigantic VRFBs of the 80s. Not only are they smaller, they pack double the energy capacity of the first generation batteries.

In addition to being more compact, the non-flammable electrolyte solution used to store energy, enables the battery to deliver 100 percent depth of discharge without degrading capacity over time.

The specs of VRFBs make them a viable option for large scale storage of solar or wind energy. Because the VRFB is designed to last through thousands of cycles it is a favorable alternative to lithium-ion, which lacks the long lasting capacity.

Gary Yang, the cofounder and CEO of UniEnergy Technologies, an energy storage solutions company, penned an article last year highlighting the advantages VRFBs offer as a large scale energy storage system.

“In these applications, they may be charged by large baseload power plants, which generate electricity cheaply but are too sluggish to accommodate sharp increases in demand during peak hours,” Yang noted. “Or they may be charged by renewable sources like wind farms, whose generation doesn’t always align well with demand.”

“Like most batteries, VRFBs can deliver power nearly instantaneously, so they can stand in for the traditional means of meeting peak demand: fossil-fueled “peaker” plants that, in comparison with batteries, are costly to maintain and operate and not as fast.”

While VRFBs offered a solution to energy grid problems, they were expensive. Five-years ago the cost of a four-hour VRFB system was roughly US$800 per kilowatt-hour.

Today, the cost has been cut in half, making it much more affordable to integrate and operate.

VRFBs and large scale storage

The first large scale VRFB is currently being constructed in Dalian,China. When completed, the battery will be the largest chemical battery in the world, with the capacity to produce 200-MW, 800-megawatt-hours.

The move by the Chinese government to invest in the storage station is part of the country’s shift towards renewable forms of energy. The station will help balance supply and demand on the Liaoning province power grid, which serves approximately 40 million people, filling the same function as a peaker power plant but without using scarce water.

There is also the potential to charge the batteries using wind-generated power, which is abundant in northern China, leading to the elimination of fossil fuels from that particular grid. The Dalian battery will ultimately provide power during peak hours of demand, enhance grid stability, and deliver juice during black-start conditions, in emergencies.

As Yang pointed out, when restarting a generator — known as a black start — requires a source of electricity to energize the electromagnetic field coils inside the generator.

Power plants usually get this energy from the grid, but when the grid is down they need a backup, and it’s usually in the form of a small generator, large scale VRFB stations eliminate the need for a separate generator because they can power the black start process.

When it comes online in 2020, the Dalian vanadium station will remove roughly eight-percent off the current load.

The Dalian site is just one of several big VRFB installations being built in China, so its reign as the world’s biggest battery may be short. Meanwhile, other countries are adopting VRFBs as well.

According to the US Department of Energy’s global energy storage database, since 2012, 70 VRFB projects in more than 11 countries have been developed.

Driving the interest in VRFBs is the push to capitalize off the newest, greenest energy solutions.

In 2012, energy storage was a US$200 million industry, by 2017 it had grown into the multiple billions since then.

Click here to continue on to part two of this series, or click here to read part three. All three parts are linked below:

- Is Vanadium the Energy Storage Solution of the Future? — Part 1

- Is Vanadium the Energy Storage Solution of the Future? — Part 2

- Is Vanadium the Energy Storage Solution of the Future? — Part 3

Don’t forget to follow us @INN_Resource for real-time updates!

Securities Disclosure: I, Georgia Williams, hold no direct investment interest in any company mentioned in this article.