With pricing peaks and valleys, a fair share of zinc mines have closed up shop in recent years. Here’s a look at how they could be revived.

Even with good intentions and a seemingly concrete plan of action, market shifts and commodity crashes can lead a mine to close.

While many mines manage to be successful, profitable operations for everyone involved, others don’t always pan out as planned. Factors ranging from a company’s balance sheet to geopolitical issues can cause a mine to have its operations halted, be put on care and maintenance or, in other cases, abandoned entirely.

On the other hand, sometimes a company will opt to breathe new life into an old mine. When a mine is revived, it can often come after the asset changes hands, with the new owner putting direct focus into renewing its worth. Other times, if a commodity’s price point makes a comeback, the original owners will choose to give their mine another shot.

In a previous article, the Investing News Network (INN) spoke to experts about what can cause a mine to shut down, with one major factor being price fluctuations. Leah Wong, senior issues and media advisor for Ontario’s Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines, described the market volatility that the resource sector can be susceptible to.

“Not unlike other global industries, mining is subject to impacts of global market conditions and variation in commodity prices for the product produced,” Wong said. “Different commodities may be subject to different market forces; however, almost all commodities are subject to global market forces.”

Commodity pricing aside, she went on to say there are several valid reasons for a project to shut down.

“There are a variety of reasons that a mining project could come to an end, including but not limited to changing mineral prices over an extended period of time, which renders the project unprofitable, the mineral resource has been exhausted and thus the life of mine has come to an end or financial hardship of the company.”

Some previous examples of this can be found in the nickel market; the commodity has faced two devastating drops in just over a decade. The first took place between 2007 and 2008 and saw nickel fall from highs of US$53,730 per tonne to lows of US$8,805 — later, between 2014 and 2016, the base metal lost its footing from peaks of US$21,150 to land near US$7,715.

As one would expect, many mines were boarded up during these times as their precious assets lost significant value in the marketplace.

While nickel has since gone on to recover — having recently reached a one year high of US$14,200 per tonne — other commodities have faced similar struggles.

The zinc story

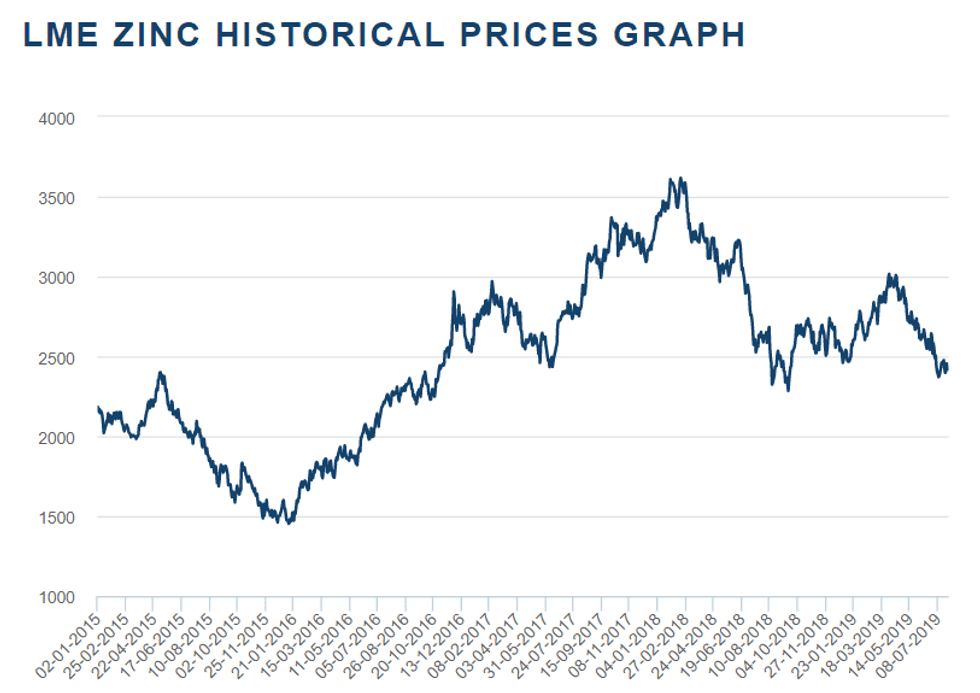

Over recent years, fellow base metal zinc has been a huge victim of supply and demand trends. In the last 5 years, the commodity has generally remained within the US$2,000 to US$3,000 per tonne range on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

However, due to the commodity’s generally low price when compared to other metals, it’s in a precarious place should its value hit a rough patch.

A prime example could be seen in 2015 and 2016: though the commodity started 2015 out smoothly at US$2,166 per tonne, it would spend the year slowly slipping to reach a five year low. This came on January 12, 2016, when the base metal fell to US$1,453 per tonne, representing a value crash of almost US$1,000 from highs of US$2,400 found just eight months earlier.

Despite the lows that zinc faced, the commodity subsequently managed a year-long rally, peaking at US$2,906 on November 28 and going on to be considered one of 2016’s strongest underdogs.

Having said that, however, it’s worth noting the cause and effect of zinc’s highs and lows. As Wong previously mentioned, a common factor in a mine’s closure can sometimes be the depletion of its resources. This was no exception in the zinc space, as a handful of major mines closed during 2015 and 2016.

Included in that list was Glencore’s (LSE:GLEN,OTC Pink:GLCNF) Black Star mine in Queensland, part of the Mount Isa Mines complex, which produced approximately 40 million tonnes of ore and 1.75 million tonnes of contained zinc between 2004 and 2016.

Finding new life

Also having shut down after the depletion of its reserves was the Century mine in Australia, which closed its doors in 2016. However, the iconic mine known for its bountiful reserves and high production rates was bought a short time later that same year by the aptly named New Century Resources (ASX:NCZ,OTC Pink:NCRE).

Formerly owned by MMG (HKEX:1208), the mine ceased operations after its ore reserves were used up. However, New Century aimed to explore the asset’s other remaining mineral assets, such as resources found in mineralized tailings.

“The Century mine … is a prime example of a mine which had reached the end of its economic life from a traditional mining perspective but retained significant value when we applied our model of economic rehabilitation,” New Century Managing Director Patrick Walta told INN.

Zinc faced another tough year in 2018 as negative sentiment swirled around the space, pushing the base metal’s price point downwards. When asked how New Century minimized the impact of zinc’s weakened state, Walta explained that the company utilized low-cost methods to retain value.

“New Century Resources’ method for extracting zinc from the tailings dam deposited over 2 years of mining at Century involves using very high-pressure, machine-mounted hoses to re-slurry those zinc tailings and pumping them to the processing plant for retreatment. This method is very low cost when compared to traditional mining methods,” Walta said.

“Of course, we’d like to see higher zinc prices, and we benefit from those prices when they arise, but long-term, our low cost profile ensures our sustainability in all price environments.”

Despite some of zinc’s pricing turbulence over the last few years, New Century isn’t the only company jumping on the restart bandwagon. On Canada’s east coast, ScoZinc Mining (TSXV:SZM) has been working to restart the ScoZinc zinc-lead mine in Nova Scotia and released an updated preliminary economic assessment in late 2018.

Earlier this year at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada convention in Toronto, Canada, Wood Mackenzie Senior Research Analyst Rory Townsend gave a presentation on the future of zinc.

While Townsend’s presentation emphasized the presence of smelters in the space, he noted some of the big mines and producers (restarts included) that investors should keep their eye on.

“We’re expecting a surge in mine production capability over the next few years. With increased production from Glencore’s Lady Loretta and McArthur River, to a host of projects and restarts ramping up such as MMG’s Dugald River, Vedanta Zinc International’s Gamsberg … and Heron Resources’ (ASX:HRR) Woodlawn, to name a few,” he said.

Though restarting a mine of any kind is no simple task, having a worthwhile resource and taking the time to create an effective game plan are two of the major keys to success.

“We invested a significant amount of effort into our early planning and design phases. This has stood us in very good stead as we refurbished the site and through our ramp up of production,” Walta added.

As of July 26, zinc was trading at US$2,421 per tonne on the LME.

Don’t forget to follow us @INN_Resource for real-time updates!

Securities Disclosure: I, Olivia Da Silva, hold no direct investment interest in any company mentioned in this article.

Editorial Disclosure: The Investing News Network does not guarantee the accuracy or thoroughness of the information reported in the interviews it conducts. The opinions expressed in these interviews do not reflect the opinions of the Investing News Network and do not constitute investment advice. All readers are encouraged to perform their own due diligence.