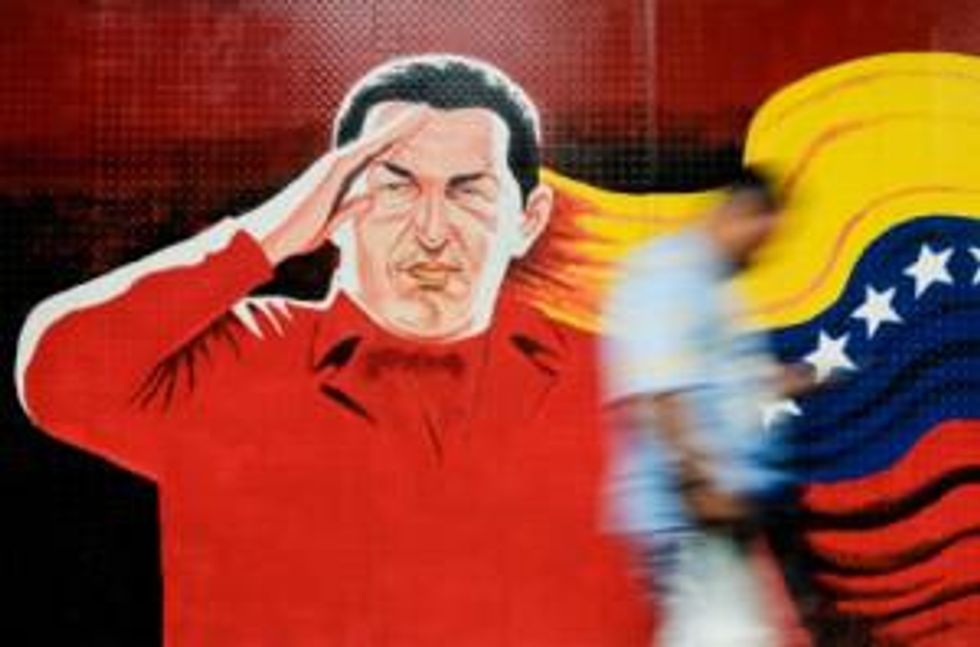

The country’s long-time president has rankled foreign miners with harsh restrictions and outright expropriation. Would a post-Chavez Venezuela be any different?

When he was re-elected for a six-year term in October 2012, Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chavez, promised to sharply increase the country’s oil production. In addition, he said he would aim to reduce Venezuela’s reliance on the US by doubling the country’s oil exports to Asia. To make servicing these markets quicker and cheaper, the government plans to build a pipeline through Colombia to the Pacific Ocean.

However, the president’s recent illness has thrown these plans, as well as other important resource policies, into question. Chavez hasn’t been heard from since his December 11, 2012 cancer surgery in Cuba. The government recently revealed that he is now dealing with a severe lung infection and “respiratory complications.”

Chavez’s inauguration is scheduled for January 10 and has raised questions about what the future may hold for Venezuela if the president, who has been in power for 14 years, can’t continue.

“We’ve never really had an official come out and provide a diagnosis,” said University of British Columbia political science professor Maxwell Cameron in a January 4 phone interview. Cameron is also director of the university’s Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions.

“There is such a high level of skepticism in Venezuela that some are even suggesting this is all untrue and that Chavez is fine. I think that’s foolish. When you have the two rivals who aim to succeed Chavez flying to Havana to swear loyalty at his bedside, it’s pretty clear they think the end is near, and there will soon be elections in Venezuela.”

If Chavez dies or is deemed unable to continue in office on a permanent basis before January 10, the National Assembly’s speaker, Diosdado Cabello, will likely take over. Elections will then be called within 30 days. If Chavez is inaugurated, but is then unable to act as president, the job will fall to Vice President Nicolas Maduro, again on a temporary basis until elections are called. Both men are thought to have designs on the presidency, though Chavez has hand-picked Maduro to succeed him.

Maduro recently noted that the Supreme Court could simply inaugurate Chavez at a later date, though the opposition disputes that interpretation of the country’s constitution, according to Bloomberg Businessweek.

Venezuela’s economy runs on oil

It’s hard to overstate oil’s importance to the Venezuelan economy; at 297.6 billion barrels, the country has the world’s largest proven reserves, ahead of Saudi Arabia, with 265.4 billion, according to OPEC.

In 2011, Venezuela’s petroleum exports added up to a total of $88.1 billion. That’s 94 percent of the value of all goods the country shipped out during the year. Oil also accounted for over 50 percent of Venezuela’s federal budget revenues and 30 percent of its gross domestic product.

In addition to oil, the country is also home to large reserves of other commodities, including natural gas, iron ore and diamonds. It also boasts around 4,600 metric tons (MT) of gold reserves, although its annual production is low, with its legal mining industry churning out about 6 MT in 2010.

Hostile territory for foreign resource firms

Despite its treasure trove of minerals, Venezuela is still a hard place to do business, particularly for foreign companies. In the World Bank’s 2013 Doing Business ranking, the country came in 180th out of 185 nations, down one spot from 2012. Venezuela scored particularly low in the categories of investor protection, paying taxes and trading across borders.

That’s mainly because Chavez has placed heavy restrictions on foreign companies operating in Venezuela. Numerous times, his government has resorted to the outright expropriation of both assets and entire businesses.

Chavez seized 988 companies between 2002 and August 2011, according to a report from Conindustria, a Venezuelan industry chamber. He also nationalized the country’s gold mines in September 2011. At the time, the biggest foreign miner operating in Venezuela was Rusoro Mining (TSXV:RML), which had two producing mines in the country, along with 10 exploration properties. The seizure sent Rusoro’s stock tumbling 16.7 percent on the day the announcement was made, according to Mining.com.

In July 2012, Rusoro filed a claim with the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes in a bid to receive compensation for its lost assets. “We tried to find an amicable solution but we never heard anything from the government, so then we decided to file the arbitration,” Andre Agapov, Rusoro’s president and CEO, told Reuters. “We lost it all. We don’t understand the situation now. We have no operations in Venezuela.”

Chavez’s nationalization decree also gave companies 90 days to form joint ventures for gold mining and granted the government a 55-percent stake.

Status quo is the likely outcome — for now

The question for resource investors is whether any of these circumstances could change if new leadership takes the reins. At this point, Cameron sees that as unlikely.

“Cabello represents the military and Maduro comes from a union background, so neither is particularly open to foreign investment,” he said. “As well, no one should assume the regime will collapse without Chavez at the helm. Look at what is happening with Raul Castro in Cuba. However, over the longer term, popular enthusiasm could be more difficult to sustain, particularly if Chavez’s party is unable to contain corruption and factionalism within the government.”

The wild card in all of this is the opposition, which lost to Chavez by 10 points in the October election. “There likely won’t be a change in resource policy until there is a new government,” said Cameron. “The opposition is divided and doesn’t have much in common except its dislike of Chavez. However, they have a good leader, and it’s not inconceivable that they could mount a challenge in the elections.”

And of course, there is also always a possibility that Maduro or Cabello could surprise. “The bottom line is these are all second-tier people,” said Cameron. “So we won’t really know how they will govern until they attain full power.”

Securities Disclosure: I, Chad Fraser, hold no positions in any of the companies mentioned in this article.